I flew to Bolivia, from Miami on Saturday, March 9 at 10:50 p.m. and arrived at Viru Viru Airport in Santa Cruz at 6:50 a.m. the following day.

Tammy Bass, and her Mother, Rosalie, were waiting for me, and whipped me off in their car, after enthusiastic embraces, to their beautiful family hotel, Las Palmas, in the center of Santa Cruz. There, we had a rich breakfast of fruits, eggs, native breads and cheeses, deserts, and an assortment of thirst-quenching juices. This magnificent, breakfast ritual was repeated every day I was in the hotel, Las Palmas, which became my home away from home for the next two weeks.

Bolivia, which takes its name from Simon Bolivar, the Liberator, is a land-locked country in South America. It was much larger, but it lost about a third of its territory, including access to the sea, in various wars with neighboring countries. It is one of the most ecologically-diverse countries on earth, and shares part of the Amazon with neighboring Brazil on its eastern border. The country possesses some of the most exotic names for places I have ever heard of in my travels; names such as Cochabamba, Cotoca, Titicaca, Tinquipaya and Copacabana. I could go on. Bolivia is another world, and, when you step into this country, you are in for an adventure.

The city of Santa Cruz, named after the ‘Holy Cross’ by the Colonial Spaniards, accounts for 70 per cent of the country’s finances. Sucre is the Capital of Bolivia, but Santa Cruz is the commercial center. Victor Hugo Cardenas, Ex-Vice President of Bolivia, was staying in Las Palmas when I arrived and came over to greet us while we were having breakfast. He was campaigning for President and that’s what brought him to Santa Cruz. “Everyone comes to Santa Cruz,” he said, convincingly.

Bolivia is a third world country, but you wouldn’t know that if you visited the tropical country club in Santa Cruz or the state-of-the-art Malls or the magnificent Plaza of International Restaurants in the ninth zone.

This country is very rich in natural resources. At one time, Bolivia was the producer of over half the worlds’s silver. It is also rich in natural gas, petroleum, tin, gold, and various agricultural products. According to Herbert Klein’s book titled, Bolivia, (which I read when I was there) the clandestine cocaine exports from Bolivia in the 1980s and 1990s generated more income than all other export products combined. I met an American who settled in Santa Cruz and who worked for the CIA during those years. He told me that the illegal cocaine exports today are much greater by far than back then. This is a source of much concern for decent families who are trying to raise their children with good family values in this climate of easy, but illicit, money.

I spoke with several families who are strongly opposed, naturally, to this drug trade and the effect it’s having on the country. They are concerned for their children, and they made a point of bringing this up in almost every conversation I had with them. The name of Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, like the name of Donald Trump in America, is on everyone’s lips. The next national election for President in October is also on everyone’s mind. The big fear of many Bolivians I met is that their country could turn into the next Venezuela.

Meeting ordinary Bolivians on the street, in coffee houses, in the hotel, and in taxis was a real joy. As one taxi-driver said to me: “La gente aqui es muy amabile.” (The people here are very loving.)

On two occasions when I was visiting different coffee shops and was carrying my tray to the door to enjoy my food outside, people got up from their seats to open the door for me and let me pass through. Little unexpected, acts of kindness like this we’re not unusual, but they make all the difference when you are a stranger in a new place. Kindness seemed to come naturally to Bolivians.

Lunch was the big meal of the day, like dinner in the U. S. I had lunch every day I was in Santa Cruz with Tammy and her parents at their home, not in the hotel. The food was sumptuous and healthy: rich in vegetable soups, salads, meat/fish, deserts, and, of course, native fruit juices. I was surprised that these culinary delights were repeated, with different variations, everywhere I went in Bolivia. The food was just exceptional.

The other meal of the day at 4:00 p.m. or later is called, tea. It is lighter than lunch, but it is a healthy meal of empanadas (crescent-shaped rolls with meat), fruits, cheese, cake, and, of course, tea.

Santa Cruz has a beautiful Cathedral, centrally located, and it dominates a large plaza which is always full of people outside, sitting on the Cathedral steps, strolling about or lounging on benches.

Inside, the Cathedral was empty. Outside was another matter. It was full of people everywhere you looked. I was grateful for the feel of the breeze whistling through the trees and having my face gently fanned on a hot, humid day. No wonder that people flocked to this place to relax and spend quality time together. Just as I was enjoying this soothing scene, I felt a sudden tug on my arm.

It was Rosalie, Tammy’s Mother and my companion, dragging me away from the Cathedral Plaza: “You need to visit the Mansion, the people’s Church, across the road. That’s where all the people go.”

I went with Rosalie. The Mansion was not what I had expected. It was not a mansion in any sense; it was an open-air pavilion where ordinary peopled gathered to pray and attend mass. It was full, inside and outside. Not like the Cathedral. Mass had just started when we arrived. We stayed for the duration of the service. It was unbelievable. This totally diverse group of people were totally united, alive and devout in their participation while the choir helped them focus and enjoy the liturgy of the Eucharist.

THE HIGHLIGHT

The highlight of my visit to Bolivia was the Jesuit missions, made famous by the movie, The Mission.

I left Santa Cruz on a three-day pilgrimage to see the famous missions in the Bolivian hinterland, built in the eighteenth century by the Jesuits. I had a driver, Jose Carlos Bascope, who doubled as a guide for me during the entire trip. It took us over five hours of driving to reach mission territory.

The Jesuit Missions are in the Eastern part of Bolivia, and you have to drive along mountainous, cork-screw roads to get there. Jose was a competent driver who knew how to navigate the curves in the roads while avoiding pot holes and on-coming traffic.

We were lucky to avoid an accident, a large truck jack-knifed in the middle of the road, glaring at us like a wounded animal. The cabin was facing us, but the body of the truck stretched at a right angle all the way into the ditch. There was nobody present, so Jose had to sneak the car through a small opening on the cabin side.

“These drivers,” Jose commented, “take too many chances.”

At last, we arrived at the beginning of the Jesuit Missions. These missions were designated by UNESCO “a cultural heritage of humanity” in 1990.

The missions were entire towns or communities of indigenous people who lived together with the Jesuits. I visited four of them. They were a unique blessing because they protected the indigenous population from slavery and from forced labor while teaching them skills to succeed and grow as productive members of society.

They were called by the Spanish Crown, “Reductiones,” where the indigenous population was rounded up into different reductions, like concentration camps. But, the Jesuit missions were different. They existed to serve the people, not exploit them as did those of the crown. And, they still exist as beautiful towns, still in use, and are a testimony to the practical love of God and neighbor. They have been described as Utopias by the French philosopher, Rousseau, and French man-of-letters, Montesquieu.

Whatever about being Utopias, the Jesuit Missions are symbols of hope regarding what is possible when people are prepared to serve one another rather than being served. They are a reminder of how difficult and even dangerous it is to do good. The Jesuit Missions threatened the status quo as the Jesuits fell foul of the politics of the Crown and the Vatican. They were cruelly expelled from the missions and forced-marched back to where they came from. Many of them never survived the hardship of the journey, and died.

What makes the Jesuit missions unique is that they offered a complete ministry to the indigenous people. They catered to soul and body, and offered a ministry of worship, resulting in magnificent Churches, and they offered a real practical ministry that took care of people’s material needs.

The first mission I visited was St. Xavier. The Church is the same as the day it was built. The huge columns that support the main structures of all of these Churches are made out of wood from the surrounding forest, and are carved in ornate patterns from floor to ceiling. There is no stain-glass in any of the mission Churches, but the interior and exterior walls are painted with spectacular images of Angels and Saints. I did not miss the stain-glass because the beautiful paintings made up for its absence. The style of architecture in the mission Churches is baroque. The main altar and side altars are highly decorated with carved statues, and the entire background is heavily embellished in sparkling gold and silver. Each mission Church is dedicated to a Saint and offers its own special artistry relating to its own patron.

Mass takes place every evening at each mission, but since we arrived in the early afternoon at St. Xavier, we decided to keep moving along and attend mass at the next mission, called Concepción.

We put our things away, after we arrived, in the Gran Hotel in Concepción where we would spend the night, and walked over to another fabulous Church.

A group of high school youngsters were being photographed, standing behind the altar. I decided to take some photos when the youngsters called out to me to join them “al centro” (in the center).

I was happy to oblige, and was photographed with them inside this beautiful mission Structure, their Church. Mass at 7:30 p.m. was exquisite. The youngsters constituted the choir, consisting of violins, guitars, drums, and a lead singer while more youngsters read the readings. The priest (from Poland) who celebrated the mass delivered a good homily, giving practical suggestions on what to do for Lent, such as avoiding idle gossip. He got two altar servers to pass out his list of practical suggestions to everyone leaving Church that day so that they would not forget his message. I took one with me.

Each mission also has a museum, explaining the lifestyle of the indigenous people during the eighteenth century. The museum at Concepción was remarkable. This was very valuable to appreciate the singular achievement of the missions during a time when the indigenous people were so badly treated by the crown in the other “Reductions.”

We left Concepción the following morning for St. Ignatius, the third Jesuit Mission. We got there in the afternoon, but José convinced me to continue first to the fourth mission Church of St. Anne, built by the indigenous people themselves after the expulsion of their Jesuit founder. I told Jose he didn’t have to leave the main road to drive to St. Anne since the little dirt road that brought you there was, by all accounts, Bumpy, Rocky, and full of holes. I was thinking of the accident earlier along the main road, and I cringed to think of what we might find on this rocky, dirt road. But, Jose wanted me to see it, and nothing was going to stop him. It was worth the sacrifice, he explained. After all, it was Lent, and, perhaps, Jose felt I needed to do some penance for my sins.

This Church was a testimony to the genius of the indigenous people who learnt their trade and artistry from the Jesuits so well that they could build a beautiful Church, in the same style, by themselves. They even built an organ that worked by pumping air, and they created their own instruments of music, such as harps.

Music is so important to the natives of St. Anne that, as we drove by, little girls were playing their violins to my great surprise, but not Jose. These were his people and he was at home with them. I recalled that in the museum at the mission of Concepción are to be found creative, music folios by indigenous people, stored away among those of the Jesuits.

St. Anne was not as spectacular as the other mission Churches since it didn’t have the elaborately, decorated high altars, emblazoned in gold and silver. The people were too poor to afford that. They built a beautiful mission Church, however, which stands as a testimony to themselves and to the Jesuits who instructed them.

We returned to St. Ignatius to spend the night at the splendid, Mission Hotel. Jose said: “this is where the King of Spain stayed when he visited the Missions.”

We broke with routine, and had a late lunch which served as our dinner. We attended mass at 7:30 p.m. before retiring for the night.

The following morning, after breakfast, we visited the Church of St. Ignatius again to see it by the light of day. It sparkled in the tropical sun as we approached its imposing entrance. This awesome, mission Church was totally reconstructed the way it had been by the Jesuits and Indigenous people over two hundred years ago. The plaza was more beautiful than the plaza of Santa Cruz Cathedral. It was the common recreational and gathering place for the entire community of St. Ignatius.

Around noon, on Tuesday, March 19, we set off on the return trip to Santa Cruz. No more dirt roads! We drove on the main highway all the way. The main roads in Bolivia are very good, and driving was very pleasant. We pass little towns and town-lands, which are protected by road bumps and barriers to slow down the traffic so people can go about their business. All these little towns and town-lands have running water and electricity, courtesy of the efficient Cooperative Rural Electrical program (the largest in the world) and the Cooperative Water Program.

We drop off for lunch at a beautiful little, tropical oasis, called St. Xavier. It was like a little bit of heaven, exquisitely designed, and the food was outstanding.

Continuing our journey, we toured two colonies of Maronites. There are over 70,000 Maronites in the Santa Cruz Department.

The Maronites, who are opposed to military conscription, were invited to settle in Bolivia. They keep to themselves, run very good farms, and are good for the economy. Like the Amish in the United States, they use pony and trap to get about, and generally shun modern technology, including I-Phones.

My last few days were spent in Santa Cruz with my gracious hosts, the Bass Family. We had much to talk about and laugh about. My hosts had never visited the Jesuit Missions, and they wanted to know everything about them.

I called my friend and good neighbor, Francisco Matado, the day before I left Bolivia to talk to him about my return flight to Miami.

“I’m all set to pick you up on Saturday,” he said.

“It’s not Saturday,” I replied, panicky, “it’s Friday.”

“Well then. It’s Friday,” Francisco said, nonchalantly.

I was glad I made that call.

He picked me up on time at Miami Airport in Friday, March 23. We had much to talk about as Francisco drove me home after a most memorable trip to Bolivia.

—Fr. Hugh Duffy

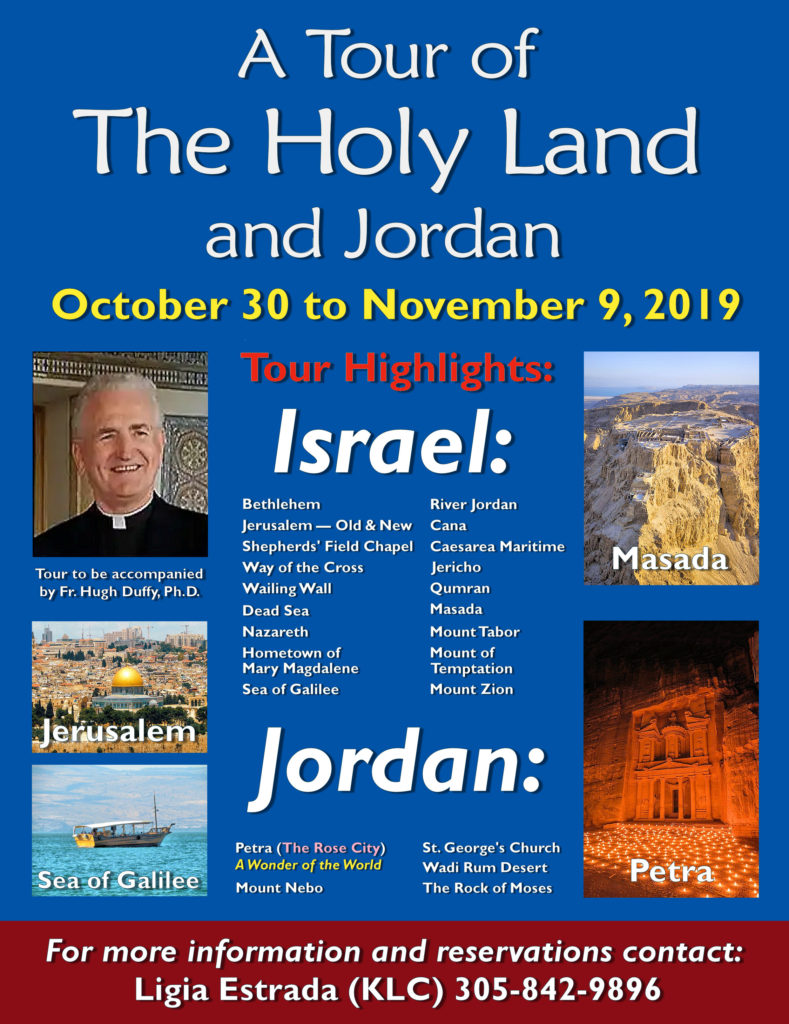

NOTE: Fr. Hugh Duffy will be accompanying a tour of the Holy Land and Jordan from October 30th to November 9th, 2019. For more information and reservations, contact Ligia Estrada (KLC) 305-842-9896 in the U.S.

7 Comments

Margaret Kelly

Thank you for this info on Bolivia. I am going to the Holy Land in September. We have to pray for peace over there.

Jan Ferencie

I so enjoyed your words and photos.

Thank you for sharing and God bless you to continue enriching our lives with these visits.

John Dalton

Your visit to Bolivia tells a beautiful story about the Jesuit Missionaries and the Indigenous peoples, but if Cocaine is the largest export, I can’t help but wonder about the lives of those around the world and the US who turn to drugs rather than God for help. When will it end.

Your Blog is a source of inspiration to us.

Hugh Duffy

Great point, John. Sadly, there’s so much evil ( cocaine, drug trafficking, etc.)existing alongside so much good in Bolivia and in today’s society, at large. What can be done about this? I think we need to be imbued with the kind of hope that does good, not evil, and that strives to make our world or local environment a better place to live in.There’s so much good being done. Let’s offer our help.

Josh Washington

Thank you for the virtual tour! I found this information very helpful. My wife is from LaPaz Bolivia, we will be traveling there for three weeks this Christmas. While there we will take a pilgrimage to Copacabana, Bolivia to visit their church, a life size recreation of Calvary and Our Lady of Copacabana. We may have to schedule a pilgrimage to the missions as well. Thank you!

Hugh Duffy

Thank you, Josh. I never got to La Paz. I was confined to the Santa Cruz Department which, as you know, takes in a very wide area. Enjoy your Christmas visit, especially in Copacabana to the special shrine there. I’m sure it will be awesome

Douglass Seruwu

Thanks Fr. Duffy, so great to know about the Bolivians, I knew nearly nothing about them. It was a great trip, and they are very nice people. I am glad you came back safely. God bless you